Stories Go Digital

Inspiring young writers in remote settings

Six weeks after Boston public schools changed from in-school classes to all-remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a fifth-grade boy and his family got home access to the Internet. Up until then, the student had been unable to attend online synchronous classes with his teachers and he was eager to join class again.

Logging into Google classroom, he was amazed to find classmates engaged in online digital storytelling workshops. His classmates were meeting online daily with Marissa, a graduate student teaching intern from UMass, to read aloud stories they had written and to discuss writing and reading different genres - narratives, nonfiction, fiction, poetry and comics. Excited, he immediately posted to Marissa, “Can we please join the writing workshop today? I’ve been looking forward to it. Please.”

We learned about this young writer and many others in Zoom-style conversations with former students that we had taught in classes at the College of Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. As we planned an online presentation for the ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education) Digital Storytelling Network 2020 Summit in June, we reached out to former students asking them to share their experiences with remote learning in public school and higher education classes.

We discovered a myriad of ways digital storytelling can happen in both synchronous and asynchronous formats, at elementary, middle, and high school grade levels, in different subjects from math to social studies, and in different genres through fiction and nonfiction. What united all these wide-ranging storytelling opportunities is a “writing process fit for young writers” - the key theme of our recently published book Kids Have All the Write Stuff: Revised and Updated for a Digital Age.

A Writing Process Fit for Young Writers

A writing process fit for young writers promotes what we call “learning from the inside out."” In this approach, students express themselves imaginatively and creatively from their own ideas as they brainstorm, draft, revise, edit, and publish writing.

The process begins as students develop initial ideas in conversations with instructors or by reading books, watching videos, or listening to podcasts, students brainstorm. Students then draft their writing using paper or screens to record their ideas. Sometimes they co-write with peers and adults. They refine their draft by revising it - seeing it through someone else’s eyes by reading it aloud to an audience and choosing to clarify what they wrote by inserting details, dialogue, or description. With the help of a digital or in-person editor, they utilize standard spelling and punctuation and, when students have the knowledge, paragraphing. Finally, they share their stories with others by publishing with paper or digital tools.

Here are a few of the ways a writing process fit for young writers can look during remote learning.

Virtual Writers’ Workshops

Marissa, the fifth-grade teaching mentioned earlier, invites her students to synchronous digital story writing workshops through Zoom meetings. Initially, she planned to share writing ideas in blog posts for students to access asynchronously, but quickly shifted to almost daily synchronous writers’ workshop meetings, when her students made it clear they wanted to have face-to-face interactions, to talk with each other and with her.

“When our school switched to online learning, I wanted to find a way to incorporate writing into our new remote to offer students creativity and choice. I thought that writers’ workshops would provide kids with a place to ask questions, discuss their lives and speak about what was happening outside of school.”

Marissa began the online meetings with questions, but, much to her dismay, no one spoke. She shared, “My students sat silently and looked at me. So I asked other questions and I received more silence.” Marissa adjusted away from this teacher-directed format by providing open-ended phrases to spark individual writing, asking students to contribute their own story-beginning phrases. In response to “One hot summer day“ she now had students respond with stories like:

One hot summer day Martin and Liam were done making their Youtube video. Sweat was pouring off them like a river. Martin said “we should get ice cream” and Liam said “Yeah we should.” So they got in their Tesla and went to Ben and Jerry’s to get ice cream. They were about to pay for their ice cream when Martin reached in his pocket to get his wallet and realized it wasn’t in his pocket. Liam said “let’s retrace our steps.” Martin said “okay.” Martin realized he had to have left it at home. They got to the house and he found it in his room on the table under some papers. He was so embarrassed. They laughed it off and left to go get the ice cream. The lesson of the story is you’ll never leave your wallet if you stop, think and don’t rush.

Two big changes facilitated students’ conversations and enhanced their responses. First, Marissa renamed the publishing portion of the writers’ workshops from from Peer Editing to Readers’ Response. Peer Editing seemed grown up and foreign and led young writers to believe they had to do whatever their peers suggested. Reader’s Response is an example of kid-friendly vocabulary or language that students easily understand.

Most students did not want to change their writing or be told what changes they had to make. Marissa further explained Readers’ Response as the time when the audience listens to the writer read their work and gives creative ideas or suggestions. Writers listen to ideas for changes, additions, and deletions, and consider whether or not to make revisions, responding with a simple, “Thank you for the idea.”

When students believed they still had control over their own writing and agency over the revision process, they were willing to listen to what other writers were saying.

Second, Marissa moved from choosing who would read next to giving students more of a leadership role. Now, after reading their own work, each author invited the next student to share and often did so by asking who wanted to read next.

Writing Math Comics

A writing process fit for young writers can also be applied beyond the language arts curriculum. Briana, a middle school mathematics teacher in a small community outside of Worcester, Massachusetts, often offers her math learners choice and surprises for assignments.

When her community’s schools closed for quarantine, Briana engage students in weekly learning experiences through synchronous online meetings and asynchronous learning posts using Google Classroom. One early surprise assignment was an invitation to make a math comic to tell the story of their journey in math class over the past year. Project criteria asked to students to: create at least four panels, tell a story about you and math, include drawings in every panel and words in half of them.

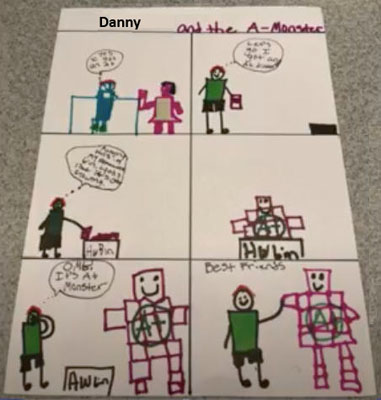

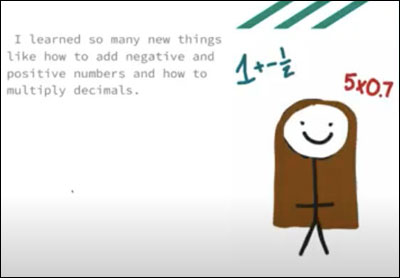

Student stories took many different forms. For example, In Danny and the A-Monster, a young boy reacts with joy after getting an A+ paper from his teacher (Panels 1 & 2). When he puts the paper in his homework bin, a remarkable transformation happens (Panels 3 & 4). An A+ monster emerges from the papers and becomes Danny’s new best friend (Panels 5 & 6). In another comic, a student proudly announces that she has learned how to add negative and positive numbers and to multiply decimals.

Briana had learned from her college experiences with us that asking students to start at the top of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Higher Order Thinking Skills — to create math comics to tell their stories — would interest them differently than if she sent them questions to reply to or requested a written explanation or summary of their experiences with mathematics. She recognized that writing and drawing that offered choice and put design into students’ hands creates an informative way for teachers to understand students’ thinking and resulting in student comments like “Math has been really fun!”

Stories of Heroes and Heroines

Erich Leaper used a writing process fit for young writers to invite creative thinking and engage his 7th-grade social studies students in the mythology of Ancient Greece and Rome. When schools closed, Springfield Massachusetts Public School teachers and students did not meet students in synchronous online sessions, and instead used Nearpod to post assignments with students responding asynchronously. To accompany each day’s assignment, Erich filmed a short video of himself greeting students, explaining history concepts or content, and introducing reading and writing activities.

For the final culmination of their unit, Erich invited students to write digital fiction or nonfiction stories using ideas they had considered while reading the myths. In a video post, he told the students, “Your story can be set in a real place or an imaginary one, and the main character can be a hero of any gender.” He reiterated that “story” is hidden inside the word “history” — reflecting the class theme that history is made up of people’s stories and that storytellers are history makers.

One young storywriter placed her main character in a fictional post-apocalyptic world, struggling with the impacts of a pandemic. The first page of her story began as follows:

It’s been 5 years. Isolation is still up because of corona. No jobs, little amount of people and the biggest problem is there is no cure. People start to forget things. Maybe because there is no school or because the corona eats your mind out and you slowly die out. But Jenna on the other hand is sick of this pandemic. Stuck in the house, no electric, no food. NOTHING. she was starving. she went to the local grocery store to find something. she hopes is not moldy and old. she found a bag of chips. "This might last me till sundown." As she thought. Sundown came along with silence. But not all silence. Jenna crying her heart out because she is alone and starving. She went to the grocery store hoping to find something again. while she was walking through garbage, she found a book. medical potions. she held it in her hand. Flipping pages as she stops on one page. "The cure for any sickness," Jenna said …

Drawing on what they had learned from the stories of Ancient Greece, the students incorporated their choices of storywriting elements into current-day stories, combining fiction and nonfiction and creating complex issues or problems for main characters to face. They encountered firsthand how history is a vast collection of stories that help us to understand ourselves and our lives.

Students Become Digital Storytellers

In Marissa, Briana, and Erich’s classrooms, digital story writing took a range of forms and genres: historical fiction, realistic fiction, fable, fantasy, mystery, nonfiction, biography, graphic novel, and fairy tale. Students chose what they wanted to write and did so enthusiastically, even given the disruptions and stresses created by having to stay at home.

The key to student involvement was how teachers organized their online storywriting activities. No matter the format, these educators found it was essential to:

- using kid-friendly language in explanations, invite students to write

- offer choice of genres and ideas,

- let young writers choose which suggestions to use or discard, and

- empower each author to express their own thoughts.

As Marissa told us, “If their daily experience is repetitive and full of the teacher’s voice, the invitation loses luster.”

Digital story creation flows naturally when adults and young writers utilize a formula for writing success of choice (young writers make decisions about what to write) + play (youngsters enjoy and want to continue the experience) + risk-taking (kids try unfamiliar genres and forms without worrying about spelling and punctuation being correct) + approximation (writers do not have to produce finished products every time). When students are given the choice to write and support to continue doing so, every youngster can become a writer right now.