Splat... Pow... Wow...

Make learning fun when students create their own comics, cartoons, and graphic novels.

While comics, cartoons, and graphic novels have been around for years, recent movie blockbusters based on comics and graphic novels, including Wonder Woman, 300, and Avengers: Infinity War, have fueled even more interest in the genre. Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel memoir of the Holocaust, Maus: A Survivor's Tale, has also helped to elevate the graphic novel to a more respected genre.

As educators, we’re always on the lookout for ways to use popular culture to engage our students. The creative application of comics, cartoons, and graphic novels provides an opportunity to connect our classrooms to the world outside, making learning relevant to students’ lives.

Finding ways to motivate students to read is crucial in our quest to build student literacy. Integrating graphic novels into your reading program is a great way to reach out to reluctant readers and help them view reading as a pleasurable activity. Nearly every teacher can tell you a story about a student whose interest in reading soared after being introduced to stories in comic or graphic novel form.

The comic book genre can help us engage students, improving literacy skills as they explore content in new ways. Kids think that comics are fun… so let’s capitalize on that interest to promote learning and improve comprehension and thinking skills!

Brain-based teaching tells us that students learn by doing. Having them create their own comics as a form of expression and communication will provide additional opportunities for learning.

Increasing Achievement with Comics

A comic book is a combination of pictures and text that tell a story through a series of panels. When developing their own comic books and graphic novels, students practice summarizing and creating non-linguistic representations—two of the instructional strategies proven to boost student achievement. (Marzano et al., 2001)

Creating nonlinguistic representations of knowledge requires students to organize and elaborate on the information. Marzano and team state, “the more we use both systems of representation – linguistic and non-linguistic – the better we are able to think about and recall knowledge.” Comics are a natural marriage of these two forms of representation.

Because comics require illustration, they validate the learning needs and strengths of visual learners who may need more than words to convey meaning. The illustrations required by the comic genre also support second-language learners in our classroom, allowing them to demonstrate knowledge even when they don’t know the words.

Summarizing involves deleting, substituting, and evaluating which information is most crucial for meaning, requiring students to engage in detailed analysis of the content. The limited amount of space in a comic’s panels requires students to choose the most significant points in a text or story. Their completed comic then provides a vehicle for assessing each student’s comprehension of the ideas in the content they are reading.

Comic Themes

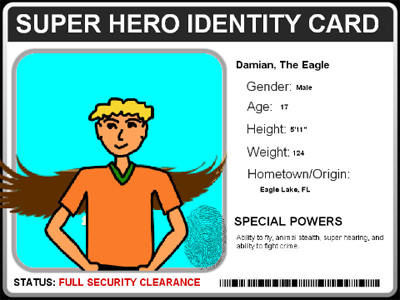

When you consider comics and graphic novels, you cannot help but imagine a superhero struggling against “the forces of evil.” Each of us has someone we admire and can call a hero. Using a heroes theme focuses student work with biographies, and provides a natural fit with studies during Black History Month and Women’s History Month.

Heroes, or heroic qualities, are also a useful vehicle for exploring the myths and legends of other cultures. We believe we can learn from a hero’s triumphs or mistakes, so a good myth or legend includes a heroic journey that we can relate to our own lives. Exploring what makes a hero and defining the characteristics that make a person a hero supports character education. Developing myths and legends of their own can help students explore possibilities for overcoming challenges in their own lives.

The Characteristics and Composition of Comics

Students can learn a lot about effective communication as they study the characteristics of successful comic books and graphic novels. Telling stories in a limited space requires comic authors to carefully consider composition, viewpoint, and character expression. How these elements are combined into text and illustrations will determine how the reader interprets the story.

The pace of action in a comic is real-time—it happens as fast the reader progresses. Students need to determine how they want to structure their story within the panels so that it progresses at the pace they intend. Using many panels leads the reader to believe that the action is occurring at a rapid pace. A single, highly detailed panel slows the reader down while providing lots of information that can help set up a future scene.

Comics also provide an opportunity to explore tense. Since dialogue is viewed as present tense, students need to be creative in demonstrating events that occur in the past. A simple caption may suffice, but age differences, dream sequences, and remote settings can also achieve this effect. As students brainstorm strategies for showing events in the past, they build stronger vocabularies and skills that will help them establish mood in their non-comic writing.

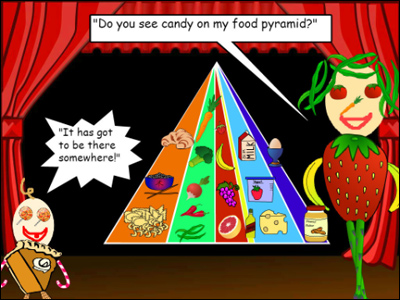

When creating comics, students learn to guide their readers’ thoughts and feelings with pictures and dialogue, building more sophisticated communication skills that will help them as they work on debate and persuasive writing projects. The space between panels also requires a reader to infer or imagine what is happening, requiring students to provide context and clues to help the reader make correct inferences.

Sequencing and logic are crucial to good storytelling, and students quickly learn that they can’t simply jump forward in time or around in space. Grouping different scenes together leads to non sequiturs, confusing the reader. A series of events that do not include the important elements of plot can lead the viewer to the wrong conclusion.

Successful comic authors also employ point of view in both images and text. When developing their comics, students need to choose between first and third person. The first-person perspective helps them connect with the reader; the third-person perspective is often more versatile. Developing illustrations that show perspective helps students create a richer mental picture of “I felt…” or “I jumped at…” This gives them more information to draw on when adding descriptions and detail to other narratives.

As students learn skills and techniques to tell their stories, they will also start to realize how the media uses those same techniques to capture viewer interest and lead viewers to specific conclusions. As they learn to succeed as media producers, students also naturally become more savvy media consumers.

Having students showcase their ideas using comics and graphic novels is yet another tool you can add to your bag of tricks to make learning relevant and fun!

References and Resources

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Westby, C. (2005, Sept. 27). Language, Culture, and Literacy. The ASHA Leader, pp. 16, 30.